Indigo Cultivation: Life at Governor James Grant’s Villa Plantation

The main export crop in British East Florida during the 1760s and 1770s was indigo. The following essay briefly explores the experiences at Grant’s Villa, the most profitable indigo plantation in the province. Located six miles north of St. Augustine and one-half mile east of the Atlantic Ocean, between the North and Guana Rivers, the plantation was owned by James Grant, the first governor of East Florida. Land clearing and planting of provisions and indigo seed began in 1768. Eventually, sixty-nine enslaved black people lived at the estate. Labor was directed by a white overseer Alexander Skinner, the white overseer, one and sometimes two white assistants, and several enslaved black drivers. The majority of the laborers were born in Africa and purchased from merchants involved in the Atlantic Slave Trade.

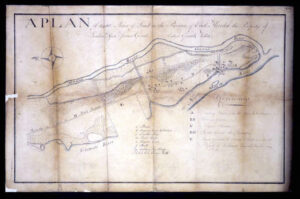

Surveyor’s map of Grant’s Villa, a British East Florida indigo plantation, circa 1784. Today the site of Guana River State Park. Courtesy of the National Archive, Kew, England.

Guana River State Park, from 1768 to1784 a British Indigo Plantation. The park is located six miles north of St. Augustine along highway A-1-A, just off the Atlantic Ocean. The North River is on the left, joined by the Guana Right on the right. Cultivation began at the south, and proceeded north each year, with clearing of the forests commencing at the end of each indigo harvest.

The most obvious thing that can be said about the blacks who resided at Grant’s Villa is that their lives were dominated by labor. As the historians Philip D. Morgan and Ira Berlin conclude in a seminal essay on black life and labor: “SLAVES WORKED. When, where, and especially how they worked determined, in large measure, the course of their lives. So central was labor in the slaves’ experience that it has often been taken for granted.”

Labor was not taken for granted at Grant’s Villa. Slaves worked throughout the year at a variety of tasks and degrees of difficulty. Spring brought the planting of indigo, provisions, and other crops. Hoe hands battled weeds with their tools in hand, while a small number of men used “hoe ploughs” pulled by horses to more efficiently till between the rows of newly sprouted plants. Mild winters meant that more of the old indigo plants would send forth green shoots, thus minimizing planting for that year.

Florida indigo plantations were normally blessed with long growing seasons that enabled the overseers to direct three cuttings of the weed, compared to only two cuttings for Georgia and South Carolina plantations. The first cut could begin as early as May, but generally began in June, and sometimes as late as July. Once the plants responded to sun and rain and began to send forth green sprouts, they would grow rapidly until the weather cooled in November and December. The second cut was generally begun in mid-July and concluded in three to four weeks. The third cut commenced in October and lasted until mid-to-late November, with overseers and laborers hurrying to finish the dye manufacturing process before cool weather in December forced a halt. The cutting and processing cycles in Florida, therefore, encompassed half the year.

Indigo plants in South Carolina, image copied from an eighteenth century South Carolina map. Courtesy Perkins Library, Duke University.

Both men and women worked in the fields cutting indigo. Once cut, it was stacked upright in formations resembling rice or wheat shocks, loaded on wagons and carried to the closest set of processing vats. At the commencement of planting at Grant’s Villa there was only a single set of vats, but as the cleared acreage expanded to the north the number of processing locations was increased to minimize the time lost carrying weed to the vats. Eventually there were six sets of indigo vats at five locations (one site evidently had a double set of vats) to process weed from fields located on both the Guana and North river sides of the peninsula which stretched from south to north for more than five miles. Because the process demanded a high volume of fresh water, the vats at Grant’s Villa were located near the inland drainage basin on the peninsula or along canals cut to drain it. In the beginning the vats were filled by fresh water from surface ponds, but cisterns were constructed later to capture rain water and runoff in the drainage canals, to continually refill the vats during the processing seasons.

Indigo production may have been based on instructions sent to Grant by the South Carolina planter Archibald Johnston, who told Grant that each field hand could manage either two and three acres of indigo plus two acres of provisions. Johnston also recommended that one set of vats be prepared for every seven acres of plants. His instructions are reprinted below as Appendix One.

Located at each of the processing sites at Grant’s Villa were three vats plus a tub filled with lime water. In the tallest of the vats, called the “steeper” or “hot tub” and measuring eighteen foot square and two feet deep, the freshly-cut weed was covered with water and weighted down by strips of board. After the weed soaked for twelve to eighteen hours (temperature was the determinant), a fermentation began in the vat, complete with a bubbling and boiling agitation that culminated in a blue or purple froth rising to the top of the water. It was the task of the indigo maker to read the signs correctly and terminate fermentation at the appropriate time. Skinner or one of the other white overseers was generally in charge, although it is clear from the letters that some of the slaves were expert as well. Becoming expert meant learning to read the colors of the froth at the top of the vat, the violence of the boils as they rose and subsided, and the obnoxious odors of the rotten weed, “putrefaction” as it was called by Skinner. Unfortunately the noxious odors continued for up to six months while all three cuttings of the indigo plants were processed. The unpleasant smells could be lessened by carrying the rotted weed away soon after it was removed from the vat.

Stages of indigo processing in South Carolina in the eighteenth century. From “A map of the Parish of St. Stephen,” by Henry Mouzon. Courtesy of the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University.

Indigo plants in 2002 at Kingsley Plantation, National Park Service.

At the proper moment liquid was drained from the “steeper” vat into the adjacent “battery” or “beater” vat. The beater vat measured fifteen feet square and two feet deep, and was slightly lower than the steeper. Workers agitated liquid in the second vat by beating the water with paddles to oxidize the solution and prompt a chemical reaction. Johnston said the beating lasted twenty-five to thirty-five minutes, when the liquid would turn deep green and appear to have a “small muddy grain.” At that moment the lime water was added, prompting the clear liquid to rise to the top of the vat while a sludge-like sediment that contained the dye component settled, (“sinking like mud to the bottom”) according to John G. Stedman who watched the process in Surinam. Once the separation was complete, the water was drained off and the mushy sediment containing the dye was transferred to the third and smaller “sludge” or “settling” vat, which usually stood next to the battery.

The third step consisted of removing excess water from the sediment by gravitational draining and pouring the sludge into cloth bags (oznaburg), and applying weights to further squeeze out liquid. When the sludge dried into a muddy paste it was worked by hand to a smooth consistency, scraped into boxes and cut into squares called indigo “bricks” and left to stand in drying racks. The bricks were covered at the top to shield them from overly strong rays of the sun which might crack and weaken the solution. During this final or “curing” phase, it was important for air to circulate around the bricks while workers fanned away the flies that congregated around the stench of the materials. Fly eggs deposited in the bricks could cause them to rot when the larvae hatched later. The curing phase could last from days to weeks depending on how dry and hot it was at the time.

Models of vats for processing indigo. Built by students at Nease High School, with teacher Stephen A. Muskett. The vats are now at Kingsley Plantation.

When the mud became “hard and crusty and no longer soils fingers,” according to Johnston, it was removed from the drying racks and packed in barrels to await transport. The barrels were shipped from Grant’s Villa as soon as a sufficient stock had accumulated at the landing on North River. Shipping normally began in September or October and continued into the first few months of the next year. The shipments sometimes went from St. Augustine direct to England, more generally via ships engaged in the coasting trade to Charleston where merchants combined the barrels from Grant’s Villa with those from other plantations and sent a larger cargo across the Atlantic.

Alexander Skinner experimented with manufacturing procedures to increase the yields of indigo extracted from each vat. In July 1772 he joked that his ultimate goal, a yield of “twenty-seven weight to a vat,” would make Grant “too rich.” Actual yields were closer to the fourteen pounds per vat achieved from 182 of the 217 vats processed from the first two cuttings of the 1772 crop. By October 23, 1772, Skinner had shipped nearly 2600 pounds of cured dye to London, had another 3000 pounds in the final drying stages, and predicted that the third cutting would produce another 800 pounds.

Skinner was an inventive planter, eager to experiment with new techniques to increase yields and profits. One successful innovation he introduced was known as the “high lime method,” which sped the clarifying process in the “battery” vat and increased yields. Dr. Andrew Turnbull perfected this method through experimentation at New Smyrna, but in the estimation of some observers the increased yield was nullified by a corresponding decrease in quality of the dye produced. Skinner also introduced a process of heating the water in large boilers to speed up the steeping and clarifying steps and to extend the processing time of the third cutting of weed as cooler December temperatures often forced an untimely end to the harvest. Skinner learned this the hard way on December 7, 1771, when a “bad freeze down to 20 degrees killed the steep in one vat of indigo.”

Other Florida planters ridiculed Skinner’s experiments with boilers, but he got the last laugh when his critics began using the same techniques. Another Skinner innovation copied by other planters was using a small stove to heat the indigo mud during the final processing phase. Cooler weather in November and December increased the time needed to drain the last of the moisture from the cakes. Applying heat brought the harvest to a timelier end and increased the yield.

With Skinner’s innovations in place for the 1773 crop, the Villa workers were able by late August to process 132 vats without halting, at a rate of five or six vats each day. The first cutting was still underway then, and in fact had to be halted briefly because some of the weed planted in new ground had not matured sufficiently. Skinner predicted that, when completed, the first cutting would produce enough weed for 180 vats. Heavy rains and winds hurt the crop some, but after the promising first cutting was completed the second growth of the weed was severely damaged by caterpillars. In late September Skinner still had hopes of recovering from the worm attacks, but cold weather came early that year and indigo making ended the third week in November. On December 17th Skinner wrote: “All hands at the plantation are employed in preparing another crop. We shall clear but little land this fall as I think it is better to put the new land in beds.”

Work for the slaves did not end when the indigo dye was finally cured; only the nature of the work changed. In December workers hurried to dry the indigo mud into cakes and pack them in barrels for shipment to London. The cypress vats were checked and patched to be ready for the next season. Fences were mended, buildings erected, gardens cleared for spring planting, citrus picked and packed for shipment. Men shouldered axes and marched into the uncut forests to clear new fields for the next planting cycle. Pine and hardwood trees were felled and sawed into boards or cut into cord wood and transported from the plantation landings on flat boats to St. Augustine. The cleared land was plowed and the furrows were worked into planting beds. Work may have been as demanding during the off season as in the indigo processing months.

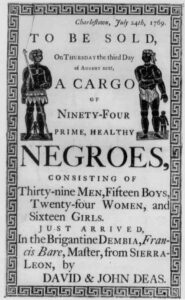

1769 Newspaper advertisement for enslaved Africans, Charleston, South Carolina. James Grant purchased enslaved men and women from merchants in Charleston and Savannah, and from ships sent direct from Bance Island in what is today Sierra Leone, West Africa. The owner of Bance Island at the time was Richard Oswald, absentee owner of Mount Oswald, an indigo, rice, and sugar plantation at today’s Ormond Beach, Florida. Image courtesy of Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite, Jr., “The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record,” produced by the Digital Media Lab at the University of Virginia Library and the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Online at http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery/.

For the field laborers the seasonal cycles would have been marked by a change in their work and tasking routines. Artisans, however, were busy at their specialties throughout the year. Carpenters had vats to build and repair, new buildings to erect and old ones to patch, carts, wagons, boats and flats to maintain, and a host of other projects of importance to the overseers. Coopers had barrels to build and line up for packing during the next processing cycle. Blacksmiths had horses to shoe, cart and wagon wheels to mend, and tools to repair.

Dick the fisherman and Black Sandy the hunter were not artisans but they had specialized tasks that continued throughout the year. Whether the two men were assigned secondary work is not clear from the record but it appears they were not. Sandy is not specifically recorded as providing wild game for the slave quarters, although that may have been part of his charge. He was rewarded on one occasion for capturing a runaway slave in the woods. Hannibal, later called an “indifferent hand” on an inventory, apparently developed a habit of absconding from Grant’s Villa and “skulking” in the nearby woods. Sandy was given a cash payment for apprehending Hannibal but the incident was coincidental to his main assignment.

Dick was expected to supply fresh fish for the slaves as well as for Skinner and the other overseers. In an October 1771 letter Skinner wrote: “Since the season of drum fishing was over Dick makes a bad hand. The bass fishing upon the beach does not go well on. He was almost pulled into the sea by a large shark and would have drowned had not another Negro laid hold of him. Since the mullet became plenty we have been better supplied with fish but have not yet seen the canoe loaded as it should be.”

Fishing had taken a turn for the better in March 1772. “Dick was of great use in the fishing way. We have frequently from eight to sixteen large drum a day.” Four months later the season for drum fishing had ended. Skinner said “the Negroes have not had much fish” but they had been supplied with pork. Fresh fish was clearly a valued dietary staple at Grant’s Villa for slaves and overseers alike. There are even entries in the plantation ledgers documenting payments to commercial fishermen in the months when Dick’s catch was less than anticipated.

In February 1781 an inventory was conducted of the sixty-seven enslaved black people owned by James Grant. Their total value was estimated at £2,953, or an average of £44 each. Forty-eight of the laborers were adults (thirty-two men and sixteen women) with average values of £61.6 for males and £41.8 for females. The eight boys on the list were evaluated at £16.5 each and the eleven girls at £16.6. When this community of enslaved workers from Africa was sold to South Carolina rice planters in October 1784, the number had increased slightly to sixty-nine. After the merchant’s commission was subtracted, the net price was £4,795, with two infants still nursing “thrown in” at no charge to the buyer. In today’s currency that amount would equate to approximately $700,000. The average price, counting male and female adults, boys and girls, as well as those who were deemed old and of little value, was £73.5. The average sale price more than doubled the average amount Grant had initially paid for the workers. Within four years of initiating the indigo plantation in 1768, profits from the sale of indigo had paid for the entire cost of startup operations, including farm animals, tools, seed, fertilizer, and the enslaved Africans. For nearly two decades after the sale in 1784, James Grant continued to receive payments on principal and interest generated by the transaction. Indigo had been the East Florida “hobby horse” he had ridden to lucrative earnings, but his true “fortune makers” were the enslaved black men and women he employed at Guana River.

Surveyor’s map of Grant’s Villa, a British East Florida indigo plantation, circa 1784. Today the site of Guana River State Park. Courtesy of the National Archive, Kew, England. Additional map work by Curtis Perrin, Jacksonville.

Guana River State Park today. From 1768 to 1784 the site of an indigo plantation.

The above essay is from Daniel L. Schafer, Governor James Grant’s Villa: A British East Florida Indigo Plantation (St. Augustine, FL: The St. Augustine Historical Society, 2000). It is based on letters in the James Grant Papers at Ballindalloch Castle, Scotland. Microfilmed copies of the letters can be seen at the National Archives of Scotland, Edinburgh, and at the Library of Congress, Washington , D.C. A second primary source was helpful: Treasury 77, the Papers of the East Florida Claims Commission, the National Archive, Kew, England. Secondary sources consulted are listed in the book’s annotated bibliography.

Appendix One. Instructions for making indigo sent to James Grant by a South Carolina planter, Archibald Johnston. James Grant Papers.

“1. Cut when blossom is full blown. Cut to within two inches of ground for a better second cutting.

2. Fill Steepers 15 inches. When cuts are down ‘I begin to stow it as if beginning a Rice Stack.’ Laths of 6 inches wide and 1&1/2 inches thick placed at 6 inch intervals to keep plant down. Cover with 3 inches of water. With inexperienced help, Under Steep by 3 to 4 hours to avoid overdoing it. Watch in warm weather for purple scum on top or [when] plants are [thin in middle] and of a clammy yellow cast and clouded. In bad weather watch for yellowness of leaf and no decay.

3. Beating — beat to a plain grain. You will see a fine blue froth at corners and sides of battery. Add lime water until grains separate from the edge of plate or cup. Make your people beat briskly until liquor is of a Mazarin color and the grain is very fine. I usually beat for 30 minutes, add lime, and beat 20 or thirty minutes more. Put in Hogsheads to make it subside better and take fewer baggs.

4. A 20 foot square vatt tends 9 acres of Indigo. For each sett of vatts of 20 feet square you need: a) 3 hogsheads and 12 baggs of a yard and a half long; b) 3 Drawing troughs of 10 feet long 20 inches wide 18 inches deep; c) 24 boxes 4 feet long 16 inches wide 2 & ½ inches deep d) clear water and 50 bushels of lime.

5. When liquor in hogsheads subsides, wet every bag and put them lengthwise, press two hands holding in the ends while two others bring liquor from hogsheads. Fill as full as can be tyed, then Press 12 hours with weights on, turn Baggs and put two above one another and add a greater weight to speed drawing. When drained, Put in boxes, have people work it with their hands until it is of equal consistency. Then it will lay until it grows thick and cracks open in the Sun. Again, you make it of equal consistency. Smooth with a paddle or trowel. At first cracking, cut into Squares of 1½ inches.

6. Curing: cut pieces and set in Sun until near hard for above one-half the thickness and then have small Negroes take a knife and turn and smooth bottom and sides, turn crusted side down on a thin board or cypress bark and let Wind and Sun get to it. Let it sit until it is hard and crusty and no longer soils fingers. Put in closed loft 2 or 3 inches on floor until mould forms on top. Put in barrels for 24 hours, empty and put on floor again (will be white and wet then) air it in the house. Mould goes away on drying….”

Appendix Two

John G. Stedman, Indigo Production in Surinam. From, Narrative of a five years’ expedition against the revolted Negroes of Surinam. Two volumes. London, 1806.

When all of the verdure is cut off, the whole crop is tied in bunches, and put into a very large tub with water, covered over with very heavy logs of wood by way of pressers: thus kept, it begins to ferment; in less than 18 hours the water seems to boil and becomes of a violet or garter blue colour, extracting all the grain or colouring matter from the plant; in this situation the liquor is drawn off into another tub, which is something less, when the remaining trash is carefully picked up and thrown away; and the very noxious smell of this refuse it is that occasions the peculiar unhealthiness which is always incident to this business. Being now in the second tub, the mash is agitated by paddles[,] seventeen adapted for the purpose, till by a skillful maceration all the grain separates from the water, the first sinking like mud to the bottom, while the latter appears clear and transparent on the surface: this water, being carefully removed till near the coloured mass, the remaining liquor is drawn off into a third tub, to let what indigo it may contain also settle in the bottom; after which, the last drops of water here being also removed, the sediment or indigo is put into proper vessels to dry, where being divested of its last remaining moisture, and formed into small, round, and oblong square pieces, it is become a beautiful dark blue, and fit for exportation. The best indigo ought to be light, hard, and sparkling.

Appendix Three

African men and women often brought with them experiences and skills that were directly applicable to their future labor in the Americas. Their adaptation to work in provisions and rice fields, for example, was facilitated by their previous experience in corn, potato and rice fields in Africa. African cattle keepers became cowboys in South Carolina, as Peter Wood reminds us in Black Majority. African carpenters, boat builders, and black smiths were aboard the slave ships that crossed the Atlantic Ocean, capable of using their special skills at American plantations as they had in their villages. That this concept may have applied to cultivating and processing indigo is supported by the observations of the British explorer, Mungo Park, during his travels in West Africa.

The following excerpt is from Mode of Dyeing Cotton of a fine Blue Colour with the Leaves of the Indigo Plant, by Mungo Park, surgeon, Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa, performed in the years 1795, 1796, and 1797. With an account of a subsequent mission to the country in 1805 ( London, 1906), 382-3.

A large quantity of wood-ashes is collected…and put into an unglazed earthen vessel, which has a hole in its bottom; over which is put some straw. Upon these ashes water is poured, which, filtrating through the hole in the bottom of the vessel, carries with it the potash contained in the ashes, and forms a very strong lye of the colour of strong beer; this lye they call sai gee (ash-water).

Another pot is filled not quite quarter full of the leaves of the indigo plant, either fresh or dried in the sun (those used at this time were dried), and as much of the sai gee poured on it as will fill the pot about half full. It is allowed to remain in this state for four days, during which it is stirred once or twice each day.

The pot is then filled nearly full of sai gee, and stirred frequently for four days more, during which it ferments and throws up a copper-coloured scum. It is then allowed to remain at rest for one day, and on the tenth day from the commencement of the process the cloth is put into it. No mordant whatever is used; the cloth is simply wetted with cold water, and wrung hard before it is put into the pot, where it is allowed to remain about two hours. It is then taken out and exposed to the sun, by laying it (without spreading it) over a stick, till the liquor ceases to drop from it. After this it is washed in cold water, and is often beat with a flat stick to clear away any leaves or dirt which may adhere to it. The cloth being again wrung hard is returned into the pot, and this dipping is repeated four times every day for the first four days; at the end of which period it has in common acquired a blue colour equal to the finest India baft.

The Negro women who practice dyeing have generally twelve or fourteen indigo jars, so that one of them is always ready for dipping. If the process misgives, which it very seldom does with women who practice it extensively, it generally happens during the second four days or the fermenting period. The indigo is then said to be dead, and the whole is thrown out….

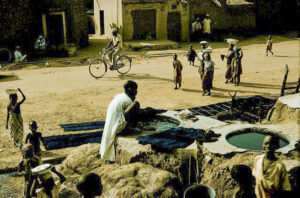

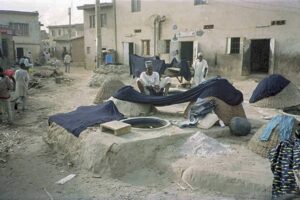

Cloth is still dyed in traditional ways by the Hausa people at the dye pits in Kano, Nigeria. Men dip cloth in clay pots filled with indigo dye, wring the excess liquid out by hand, and leave it in the sun to dry. The Kano dye pits have been in operation for 1,000 years.

Appendix Four

A Sample of British East Florida Letters

Grant’s Villa, the indigo plantation owned by Governor James Grant, was a 1,450-acre tract located approximately six miles northwest of St. Augustine. The tract was bounded east and south by the Guana River, west by the North River, and north by vacant land. Beginning in 1768, Grant’s enslaved Africans cleared six-hundred acres for indigo cultivation. Indigo weed was processed into dye at six sets of vats spread out among the fields. Structures at the plantation included two dwellings and a kitchen for the overseer and his assistants, stables for horses and other plantation work animals, blacksmith shop, large barn and indigo house, fowl and pigeon coops and houses for the enslaved black men and women. In his memorial to the East Florida Claims Commission, James Grant said all of the structures were of wood-frame construction.

In addition, the plantation contained two orange groves of about one-acre each planted in 1769-70 with lemon, lime, and sweet and sour oranges trees. Grant said any vessel capable of clearing the bar at St. Augustine could sail to the good cabbage tree wharf at the Grant’s Villa landing.

Prior to leaving East Florida for London, Governor Grant hired Alexander Skinner, a migrant from South Carolina, to oversee Grant’s Villa. The governor told Skinner in an April 27, 1771 letter: “You are to have sole management of my Negroes and plantation.” Skinner was to retain two white assistants to help manage the laborers at the plantation, Captain James Wallace, a ship captain temporarily without a command, and Richard Sill.

A ship carpenter in St. Augustine named Poole, was hired by the governor to build a flat for the Indian ferry at St. Sebastians Creek, and to also make a flat, or barge, to carry wood from the Villa to St. Augustine. He also wanted a general purpose carpenter, a white man named Cowie, to continue at the Villa for several months until he finished work on a set of indigo vats. Cowie was also expected to train Leander, one of Grant’s enslaved men purchased as a youth in South Carolina, to do all future carpentry work.

Skinner was also given authority to assign “Dick the Fisherman and Black Sandy the hunter” to provide food for the overseers and laborers at the plantation. In addition to food produced at the plantation, Skinner was given a budget of £50 Sterling a year to “set a table for yourself, Capt Wallace and Sill.” The governor expected in return, that Skinner would send to England “indigo remittances, free and clear,” and plenty of them.

Governor Grant never returned to East Florida, but he was kept informed of activities at Grant’s Villa through the numerous letters Skinner wrote from April 1771 until his death in March 1779. Following Skinner’s death, David Yeats, a medical doctor and business agent for James Grant, began sending newsy letters concerning plantation affairs.

The documents in Appendix Four are excerpts from letters written to James Grant by Alexander Skinner and David Yeats. They focus on plantation affairs and contain important information on agriculture and slavery in British East Florida. The excerpts are primarily direct quotations, but for purposes of clarity and brevity paraphrases which retain the meaning of the original text are included.

The letters are preserved in Treasury 77, the Papers of the East Florida Claims Commission, at the National Archive, Kew, England, and in the James Grant Papers at Ballindalloch Castle Scotland (now microfilmed and available at the National Archive of Scotland in Edinburgh, and at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 15 June 1771:

I take the opportunity of a sloop bound for Charles Town to let your Excellency know how we go on the plantation. Since your departure we have had no rain except a few light showers at the end of last month when we were obliged to replant in many places, some of which have not yet come up. A good deal of what had been previously planted was destroyed by the dry blowing weather. The South point has a good appearance and some places in the North and the Negro fields look tolerable. Our plow lands have stood out the worst. The little which has withstood the drought looks healthy and strong except in the old field by the Negro houses and that will produce nothing but pursley. It was replanted the 9th and 10th of May but has come to nothing and I shall plant it with peas if we have not had rains very soon.

The potatoes look very well, the corn is bad, among which we planted peas and must plant as many more as we can in the spare ground for our chief dependence for provisions must rest on the old. The indigo oats are all ready and I intend to begin to cut about the end of the month. But I am much afraid we shall not have the quantity of the indigo I expected.

Pool the carpenter has been detained in town beyond his time by a boat he had to finish, but he has now begun upon our flat and it should be ready in good time.

I received by Mr. Yeats on his return from Charles Town the broker’s opinion of samples of your indigo and Mr. Richard Oswald’s sent to London by John Gordon. And of a sample of Spanish flora marked from 10-12 shillings a pound, and as with respect to your indigo I am convinced the broker is no judge for I have compared the best of the sample of Spanish flora with some of our indigo and it is not inferior in quality; though it does not appear so well to the eye at first since it is not done up in the flora way.

Skinner to Grant, Grant’s Villa, 15 October 1771:

Summer has been exceedingly dry and I finally see that this land will do nothing without frequent rains. You will see what sort of weather we had when we were obliged to deepen and enlarge the North Pond five different times above four feet. I could not have believed it was possible for that pond to fail, except we often labored under the double disadvantage of stinted weed and dirty water, for after digging our ponds we had not had to let them. That means the indigo was not as good as it would have been. A lot of weed produced but 88 vats and many of them were only slightly filled. A second lot produced 108 which had an average yield of 7 pounds or 1372 weight….

Between the first and second cuttings I went out to the St. Johns [to view] Mr. Gray’s plantation, and the the weed growing at his plantation put me out of the concern with our own. Some indigo he had planted on perfect pine barren by way of experiment was only equal to the best of our second cutting. We have not yet begun our third cutting as we were rather late with our second. But by appearance of the weed if the weather proves favorable I believe we should make about 500 weight, equal to that of last year on average, in hopes above 7 weight [yield per vat], if we get safe through our third crop….

We have almost totally failed in point of provisions, not above 300 bushels of beans and 200 bushels of corn from upward of 80 acres of land planted in good time and properly tended. How the potatoes will turn [out] I can not justly say. They look tolerably well. [Interim governor] Moultrie was here yesterday and said they should serve us four months. The corn bought of Harris proved bad; we were obliged to allow the Negroes 3 pints a day which run us short. We were obliged to get a supply of 50 bushels of peas from Mr. Mann to be repaid in kind when the crop is taken in….

Among other things we have been rather unfortunate in the death of Negroes. Little Jack died very suddenly. He ran away and stayed about town for a fortnight. I had him ketched and brought back to the plantation, but he pleaded very earnestly and was pardoned on promise of better behavior, but soon transgressed. Sill tied him up and flogged him as I understand pretty severely. When taken down, it being hot, it seems he drunk a rather large quantity of cold water and that I imagine to be the principal cause of his death which ensued in less than an hour after.

Sill was very melancholy on the occasion and came and told me at the North vats what had happened saying that it might be represented to you in a bad light and sooner than have any blame he was going to pay for the Negro. I told him I did not know how that might be but as such an unlucky accident had fallen into his hands [I] hoped he would take better care in the caution of that part of his office.

Jamie Lowe’s child is dead, supposed to have been killed in the night by lying upon it. Three children have been born since your departure, Leander’s, Tom’s, and Doc’s. Leander’s died immediately after his birth and Tom’s about a month old, and Little Jack’s, one of the St. Johns Negroes, died of a malignant fever.

Since the season of drum fishing was over Dick makes a bad hand. The bass fishing upon the beach does not go well on. He was almost pulled into the sea by a large shark and would have drowned had not another Negro laid hold of him. Since the mullet became plenty we have been better supplied with fish but have not yet seen the canoe loaded as it should be.

The greatest part of the orange trees are dead. I design to plant another clump in lower ground as I don’t think the high soil agrees with them. Many of the mulberry slips are dead but you will be supplied with fresh cuttings from the large trees which seem to thrive quite well. The Guineas grass thrives extremely well, not withstanding the dry summer, and looks much better than your garden in town. Mr. Forbes [the Reverend John Forbes] says it is as good as he ever saw in Jamaica. I have a great deal of seed and may have as much next year as we please. We had some tolerable melons and have now a small quantity of pumpkin.

Your flat is almost finished. The sawyers are now employed in getting the Negro houses built which must be done by next winter. The Carolina vats are entirely rotten. We have had no use of them this season. Plank and scantling for another set must be got ready against next year. A drain is cut from the North River to keep the deepest part of the plantation perfectly dry. And we must clear some land adjoining to it to enable us to make something next season, for some of the old ground has refused to grow peas. Even the field adjoining the Negro huts that was twice plowed and dunged when indigo totally failed and was then planted with peas, has produced nothing of a crop.

I’m going up to see your 500-acre tract on the head of the Guano. I have been told that it contains some good land. If that is the case I would wish it nearer this place for I’m much afraid we will never be able to cut any great figure on this land with the cow manure and with our seasons. However nothing shall be wanting on my part as far as my knowledge of planting extends. The marsh mud I think will answer for manure for a small quantity laid on last Spring made a visible difference upon the indigo, and I intend to lay as much as can conveniently be done on the most contiguous land as soon as the cutting is over.

We begin to cut in a few days and the pieces of indigo shall be cut longer. Our size in general is bigger than that of last year.

Sill had commissioned for a wife before you left the province, who has since arrived. We live pretty agreeably though the lady is no great favorite of Captain Wallace nor mine.

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 7 Dec 1771:

A bad freeze down to twenty degrees killed the steep in one vat of indigo…. Our potato crop is good, we have raised 800 bushel, but we still will need to buy enough for two months of provisions. Corn very expensive here and in Carolina. Sill says it is your fault for not letting him plant the corn crop earlier.

Skinner to Grant, Grant’s Villa, 7 April 1772:

I had honor to receive your letter of January 3 on the 31st ultimate, and I am glad you are well and satisfied with our endeavors respecting last year’s crop. We must try to better it or you will get nothing by planting. You will receive enclosed a rough sketch of the plantation so you will be better informed how we were employed during the winter and know how the land is planted. We began to plant the indigo the 24th of February and have almost finished. We must soon stop as the weeds are getting up and the different fields begin to require attendance.

The season hitherto has been very backward. Last year we had a very fine season. At present it is more like winter, cold nights sometimes frost and blowing. A Northwester hurt our light ground. The seed in many parts of it blown out of the drill and scattered over the ground and in many places covered to the depth of three or four. We plant late as you may recall being practiced in England which will certainly be of use here, especially in the light hammock lands. I intend to try it if we should be obliged to replace our indigo which has always been the case.

Dressing the ground causes it to retain moisture longer and by that means the seed comes sooner up and has a better chance to establish its roots before the dry weather penetrates below it, for then it must die. But nothing can hardly protect it while young from the savage of the northwesters we have had this year and to which we lie so much exposed. We have had several gales at northwest that blew so hard as to tear up the solid ground that had not been hoed, which I had planted [that way] on purpose to secure it from the wind and that way the plant comes up as well and is not otherwise so much hurt. But you will say that the planters are always finding faults with the weather and that I am full of complaints, therefore I shall say no more on that subject.

The 46-acre tract joining the north and old Negro fields seems to me as good land as any on the plantation. The little field on the Guana side is much of the same nature, but rather lower and may be helped by a small drain if it is found necessary. If this field answers, say we get from 40 to 50 acres between that and the fence, [then we] must proceed gradually up along the Guana.

The Negroes have been kept hard at work clearing through the winter but where they have been at work the timber is heavy and cutting it up in cordwood makes considerable difference in the quantity of ground. However we will have [only] so much planted as can be tended. Sill is much afraid of the weeds and would have left off planting some time ago but I could not agree to that for if we have not plenty of land in culture, it will never do. We have about 60 acres of new land this year besides some new land on the point being totally planted with indigo, and the rest in indigo and provisions. As you will see by the sketch as soon as the weather is tolerably favorable I may venture to promise you 3000 weight of indigo and enough of provisions.

The land at Barbain I’ve lately been over is not a bit better than what we now occupy. I’ve likewise been around your tract at the head of Guano and do not think much of it. There is a small matter of tolerable hammock a piece of low marsh, something between salt and fresh, which I believe is capable of improvement but at a great expense. The rest of the tract is nothing but scrub thicket. The lands intended for Major [Taylor] I have never seen but shall take a look at it and if it is good for anything shall lay a small bit of it in indigo.

I have only sold about a hundred cords of wood and have not received a farthing of the money except for a few cords Peter Bachop had at the landing. I was obliged to depart from your instructions to sell none but for ready cash, otherwise I would not have sold but twenty cords. I must beg of Capt. Wallace to collect the money. He will not easily be denied as he is not familiar with the purchasers.

I have been careful to incur as little expense as possible since you left us and there will be some bills drawn on you for provisions and other things. Iron work, pitch, tar and oakum for the two vats have been expensive but provisions have been the heaviest article. Provision has been excessively high both in Carolina and Georgia, and is not to be exported from Georgia at the time. Both town and country here seem to be threatened with a kind of famine and for that reason I made my last effort to raise provision this year. Potatoes have been of great service to us, they would have been of more had not some of them spoiled upon us after they were dug up, occasioned I believe by covering so many of them in the hills together.

Dick was of great use in the fishing way. we have frequently had from eight to sixteen large drum a day. There is not now above three weeks provisions on the plantation, what is worse we are not yet supplied with corn….I wrote to Charles Town and asked Mr. Alexander to let me have some.

Sill upon the whole does pretty well, and I don’t know [that we] could readily meet with anyone here who would answer much better. He has had a pox for the last twelve months but has still attempted his business and he is less cruel to the Negroes since the unhappy affair with Jack happened. The peas I had last year by Mr. Mann shall be paid in the way you mentioned. He was exceeding glad to receive your compliments. He still remains with the contractor Floyd. Alexander is the principal agent. I sent the indigo to Mr. Gordon and told him to take the proper steps for insurance….

We added marsh muck to two places that did not produce the previous year. We do this as experiment that may prove to be of value to the plantation. The trees in the orange grove which were killed to the ground last winter have taken roots. I have collected plants wherever they were to be had, supplied the old grove and planted another to northward of the house. Mulberry trees in a good many slips do very well and many more slips have been planted. Poole has just finished the ferry flat and will now [go] about a boat for the plantation.

Whites and blacks are generally healthy. Jamie Lowe has got another son. If you had more women they would breed much faster and strong wenches don’t lose much time on account of having children….

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 2 July 1772:

I’m pleased that the North River crop turned out so well. Indigo is by far the most profitable to the planter. But the brokers who set prices are rogues and fools. If you dress up an offering, like I did with Mr. Grays’, the brokers pay more even though it is no better quality than in the natural state.

The crop promises to do well this year. If we could make 27 weight to a vat at 8/1 you would soon be too rich with the profits of your plantation, but that cannot be done.

It was very cold at the end of third cutting. The stems of the weed were quite small, mostly leaves went in the vats, which proves it is the leaf which produces the indigo and not the stem. There was much putrefaction after the beating, chiefly in the draining, pressing and drying, which may have been prevented if we had a method of heating….

Both whites and blacks at the plantation are pretty healthy. We have succeeded in raising poultry this season, Mrs. Sill took the management of that part…. Pigeons do pretty well although they eat more provisions than they are worth…and we have fish at times. Since the season for drum fishing the Negroes have not had much fish but they have shared pretty largely in some [illegible word] pork which they shall always have when there is any in store. We would like to have been [short provisions] but Mr. Gordon sent us a pretty good supply. Mr. Yeats plan failed as I expected. Our corn comes lower by a shilling a bushel than anyone has sold here this year though the price stands about four shillings. We have hunted up one of your cows in Diego which was sufficient for our family as neither Wallace nor I love milk, besides more would be troublesome in the present standing of the plantation situation, as the guinea grass was all killed last winter, though we have similar growing from the land.

I have got Sill pretty well under command and must keep him so….Not a drop of rain during the months of April and May, we have been obliged to plant over and over again. At last our seed failed and I was obliged to send to Charles Town for a supply of three bushel. The month of June has been very favorable. I am in hopes of the weather continuing. If it continues good we shall do something yet, though the weed is very backward. Some time ago I would very gladly have retracted the promise I made you about 3000 weight yield but I will still attempt to fulfill it.

We begin to cut the weed in a day or two. Leander has put up the vats without the assistance of a carpenter. Extra help will not be wanted until the second cutting. That was done during the very dry weather. We have now the best corn that ever grew on the plantation. I have inspected the land intended for Major Dunn, which is good for nothing except for the timber on it. The soil we now occupy is very bad and I should be very glad to have some Negroes put on a better spot, both for my credit and your advantage….Your land is miserably poor and never will do anything with the generality of our seasons.

I’ve been busy for some days past on the public accounts which means that I have not made out your plantation accounts, which I intended to have transmitted by this opportunity. I shall pay off bills with the wood money as far as it goes and send you a clear state of the whole. Next year it will not be so expensive for Poole’s wages and sundry articles for the two flats mounts up…[and it is] not properly a plantation expense.

Skinner to Grant, Grant’s Villa, 21 October 1772:

Captain Lofthouse sailed to England and carried aboard 2579 weight indigo equal in quality to last year’s average, although the average to vat is much higher. The first cutting produced 87 vats and the second 130, in all 217, of which 182 makes up this shipment.

[I] received a boiler but it didn’t come until after the second cutting. We shall see by the sale of indigo what effect it has. I have built a small stove for drying the indigo when the weather gets cold which will be of some use. We have finished a few vats of the third [cutting] and shall go on as fast as we can. The caterpillar threatens us again and I am afraid will do us some harm. Our new land turned out very indifferent. I hope it will answer better next year. I begin to clear away very soon on the Guana ridges where there must be from 100 to 150 acres of land against next year as most of the old land is quite gone [worn out]. Marsh mud will answer for manure but the land so manured must not be planted till the year following. My second cutting of indigo on the mudded spots turned out much better whereas the first cutting was much worse.

The Negroes are pretty healthy. I am much pleased with the crop of provisions. I can not justly say how much corn we have as it is not all got in. There have been 1000 bushels [gathered], about 200 bushels of peas and a tolerable appearance of potatoes so that I am pretty easy with respect to provisions.

The wench Ava who had long been in a declining state died some time ago. Poole has finished a very good boat which will answer us well to ferry you and your company from Barbaine or give you a pleasant sail from town to the plantation, if we should have the happiness of seeing you once more in this country.

I have replaced the Carolina vats with a new set and am thinking of getting ready the materials for a new set next spring….

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 30 Dec 1772:

Frost broke us up on 4th of this month, causing some damage to our third cutting. Next year I plan to push for 4000 weight.

We have 120 acres of new land now cut down on the Guana Ridge extending near to a mile and a half along the River. This will keep all hands busy till near planting time….

The Negroes on the plantation are at present strong and fat to which the new boat does not a little contribute as Captain Wallace takes frequently a sail over the bar and catches bass in abundance. Forty-three large fish were carried to the plantation on Christmas eve, about thirty weight each, which with the carcass of beef sent the next day was no bad cheer on that occasion.

I should be glad if you would order around on the first vessel bound for this place four pieces of strong duffels as Mr. Paine’s blankets were but indifferent and very dear. We stand in some need of a supply which at present we will choose to make it over the winter. [Mr. Paine’s clothing, especially the breeches, are inferior] and the Negroes must have something on their legs in the winter.

Once before I wrote to you that a few more wenches would be necessary on the plantation. I now beg leave to remind you of it. The proportion of the women is certainly too small for the men and this I take the be the cause of their not breeding. But there is another evil that arises from it that is every day increasing. Viz. [That is that] the boys are now grown to men and they with the other old Negroes who have no wives make free with the married women. The husbands find them out and quarrels ensue. Robin was sometime ago near to having his skull split by a stroke of a hoe he received from Toby on this account, besides many other quarrels of a like nature which frequently happen.

Skinner to Grant, The Villa, 17 April 1773:

I received your letter and am pleased that you are satisfied with the way I am running the plantation. We finished the first planting two days ago and have yet an additional quantity of land in culture this year by 150 acres on the Guana planted with indigo only. This is a great deal of land to tend but we can do it, as 70 acres of old indigo has stood the winter and that does not require half the attendance of young indigo. The north field and old Negro field being worn out for indigo, I have thrown it into corn and potatoes and have three hoe plows at work now. By this means I think I will be able to manage the indigo [and keep down the expenses from purchasing provisions. Some of this is very bad land, but] I must rest satisfied and do the best we can….

Mr. Yeats intends to transmit to you your accounts and vouchers up to 31st of last December which I am sorry to say mount too high, although there are no expenses incurred that could have been well avoided. Firewood does not sell if we have it, which makes some difference, but this year your expenses will not be great as there are no provisions to buy or wages to pay for a ship carpenter….

Please order me another boiler, one to hold about twenty gallons more and with a large cock at the bottom. It may be iron or copper if the cock can be fixed at the side close to the bottom, in such a manner that it will run off all the liquor when the boiler stands upright. Such a form as this will require is not common to iron boilers because the bottom must be perfectly flat, however on the whole I imagine copper is nearly as cheap for when you want to sell it you recover a good part of the money it cost….

Please also order me two plow shares of a patent plow described by Mills in his husbandry volume one, page 257. A plow of the same construction was bought at Mr. Danskin’s sale. The wooden work can be done at the plantation and our blacksmiths will make the collars. But all of the blacksmiths in the province could not make one of these shares. I also need a pair of smith bellows and an anvil and a small sledgehammer and two or three hand hammers, a vise, and a few files. I think this would be a saving to the plantation as we could continue to do a good many small jobs ourselves without the loss of the Negroes time going to town for every trifling thing that is wanted. Besides paying extravagant prices.

I should have sent you a sketch of the land cleared last winter, but as it is only a long slip from the top of the bridge I thought it was not necessary. My intention is to clear a little in the coming winter or instead I shall put our new land in good order and renew as much of the land as we can with marsh mud.

I can give you little account of the Negroes employed in town as I have never taken notice of them. Alexander as far as I know has been diligent in the baking. I have let him have flour out of the fort sundry times when it has been scarce in town. Mr. Yeats complains sometimes of Peg’s not giving him money, and threatens to send her to the plantation. Sue is hired at present by the month to a Mr. Wood, he to to have her and keep her.

Captain Wallace begins to be weary of staying ashore and says that he has no prospect of living but by way of his profession. It would be a loss to him if he remains much longer in his present situation, as he may wear out of practice. I have told him several times that you intend to do something for him. When it is convenient he should quit your services, which he says he will not do until it is suitable to you. He is a worthy young man who has been useful about your plantation both as an indigo maker and otherwise.

I was down at the Musquitoes in February and was pleased for their lands. I am firmly of the opinion that in all the province there is not a body of land equal to that on the Tomoka. Plenty of fine indigo hammocks and exceeding good swamp and fresh marsh. Mr. Oswald will have indigo ready to cut about the end of May, if there is anything of tolerable weather. I have promised to go down there about that time and stay with Robinson for about a week.

Skinner to Grant, Grant’s Villa, 30 May 1773:

We have been plagued by a rotten drought, but rain will come. Whites and blacks at the plantation are healthy, although Dr. Yeats is ill and went to Rhode Island for four or five months.

At present we have only one set of vats. Leander is fixing them. When he finishes, I will have made a cistern for every two set of vats that will hold water for two steepers. In this [manner] I think I can prepare the water better than it could be done in the pond, and the vats will be filled in five or six minutes.

Skinner to Grant, The Villa, 22 Aug 1773:

It has been very dry this spring, no rain fell as of 24 June. Indigo seed sown died, so did the corn, which was partly lost. Then the rains came on 9 July, and the old weed did great, with fresh stems and luxuriant growth. We replanted extensively.

We made 132 vats without halting at the rate of five or six vats per day, then had to stop to clean some of the new ground as the weed was not quite ready. The first cutting will do 180 vats and the total crop should be 5000 to 6000 weight of better quality than last year.

But we did lose half the corn to the drought but it will be alright since I had extra fields of corn planted.

I have been wishing for a vessel which has every day been expected consigned to Mr. Gray with Negroes that I might get the additional number of women you ordered, for I could have employed twenty Negroes to good advantage this month past. I have bespoke these wenches of Mr. Penman who acts for Mr. Gray in his absence.

. . .

Your sloop is unfit. It will cost more to repair it than it is worth. The problem is not worms, but the floor timbers and upper works are decayed. I sold the new boat. It was good for going back and forth to plantations, but of no use for fishing. John Moultrie paid £46 Sterling for it, which should buy a good Negro woman which will cost nothing for repairs, nor be so liable to be consumed by the worms….

The Negroes in town behave tolerably but I had no instructions from Mr. Yeats concerning them further than to see that they were constantly employed and therefore I have made no demand of cash nor never had any from him on their account. Peg accounts for herself, and for Sue, and Alexander accounts for himself, but how they have paid I know not. Mr. Yeats has frequently complained of Peg and Sue and threatened to send them to the plantation.

Skinner to Grant, The Villa, 17 December 1773:

I finished indigo making three weeks ago when it became too cold to continue. We suffered high worm damage in the fall and will probably produce only 2000 weight for the year.

The ship carrying our clothing hit the river sandbar and the clothing was lost. Right now we have about half the clothing needed.

A ship bound to this place with slaves consigned to Alexander Gray was cast away off Smyrnea about six weeks ago and out of 110 Negroes only seventeen were saved. The survivors were brought here and sold by James Penman. They sold high for average price of £52 Sterling….

All hands at the plantation are employed in preparing for another crop. We shall clear but little land this fall as I think it is better to put the new land in beds which should produce a better crop next year, though I shall miss Captain Wallace [when]…it time for indigo making. I wish you would send me the young man you mention so that I may teach him to make the new crop. I do not expect that Sill will stay longer than this year, as he intends to go upon shares with Thomas Morris….

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 8 February 1774:

It was a very cold winter, causing ninety percent of your high land indigo [serious damage]. The indigo there has died. We will make it up by planting early. The ground is all in good order, after we worked it this winter. No new land was cleared this year.

Captain Wallace bought a sloop and is going in the Carolina trade. Sill has given notice so now we must find a person to fill his place at the end of June. I think he will repent leaving the Villa so soon but he has learned to make indigo and has saved money. He wants to purchase Negroes to plant with somebody on shares. He wanted much to go away at Christmas but I could by no means agree to that as an hours warning had not been given. He is a good overseer. Upon the whole I will be sorry to part with him, were it not on account of his wife. I have been very civil with them both but she is much too fine a lady to live upon a plantation. A reason given for her leaving the plantation is that it would be a reflection on the children if their father was an overseer. I have partly agreed with Mr. Moultrie’s faithful Irishman Sampson to supply the place of Sill for a year, starting the first of July, and should be glad if you sent out the young man you mentioned, or any sober attentive person that you could be sure of for some years. To be an overseer is not soon learned and it does not answer to have a fresh one to look for each year. I shall be at a loss at indigo making this year as I hope to employ more vats and there are fewer people to attend them. I should not be afraid if you were in the old house and I could then be constantly on the spot.

Your account of expenses are not yet made. I think on the whole they will be moderate. This year past the account to December 1771 and to December 1772 should have been transmitted long ago but Mr. Yeats has only lately returned from the North….

No Negro vessel has yet arrived though daily expected. As soon as I can raise the necessary funds, which I expect can be done soon after the arrival of our new governor, I shall take a trip with Wallace to Charles Town and make a purchase….

Mr. Yeats complains the Negroes employed in town make bad payments and I believe are not doing much good. Alexander is turning old and infirm. Peg and Sue feel worse times on account of the very few troops in the garrison.

Skinner to Grant, The Villa, 10 November 1774:

The indigo crop in general in the province has turned out very well this year despite the extreme dryness of the months of July, August and September. At Grant’s Villa, however, the weed was very well established and we should have in some measure got the better of the dry summer had not the caterpillar attacked us early in October soon after the rains set in, which effectively [caused] our misfortunes. We were then busy with our second cutting, the latter part of which suffered….

The worms eat up every bit as fast it shoots so the plant is no further use as it is impossible for it to grow till these insects either perish for want of food or the birds pick them which does not happen….By this means we have suffered greatly in our second cutting and almost totally lost our third. But you will be disappointed with this disheartening news and I will say no more about it.

Skinner to Grant, The Villa, 24 December 1774:

I have shipped you 4600 wt on the “Betsy” bound for the port of London. Another shipment of 5460 weight and of good quality even though it was made in cold weather. I am willing to get as much as possible but no art will make it good after the middle of November. The quality would been better if Wallace been with me, although I offered any wages in reason he could ask for the season.

Sampson is now a good indigo maker and as good an overseer as Sill so that I am quite easy with respect to our operations next year. I had a very good boy with me during the last indigo making, Randolph Stewart, the son of old Robert Stewart, whom I had for instructing him. As he has behaved well I must give him some small acknowledgment. Mr. Bremner will supply his place the ensuing season….

The South Point must have some rest as I intend to turn it into a pasture for the work horses. I shall have about eighty acres of new land to make up for that deficiency. I thought we had enough provisions last year but was obligated to buy about 100 bushels of corn to bring us into the new crop. Our falling short owing somewhat to Sill who was not so good his last six months as formerly. We have a bad crop of potatoes this year, but have more corn than ever besides 100 bushel of Guinea corn, thus I can return the corn that was borrowed or sell it to repay, but I can’t part with corn until I’m sure we have enough. Horses must be fed and they eat a great deal. Corn can not be had to the north of Georgia which drives up the price here.

The first land replanted, which is at present corn fields, was much improved by plowing and manuring with rotten indigo weed. I intend to try this with indigo fields next year…. We may tend this land to advantage with the hoe plow made for that purpose. I also plan to extend the trial with marsh mud, although I worry it can not be carried beyond a twenty grade length for want of horses. I was obliged to buy two horses in the Spring at £8 each as it would have hurt the young horses to work them so soon and it was necessary to have them for the plows. We have sundry young horses which may be ready to work this spring and we have others coming on but I could wish in addition to have two or three good breeding mares as the range is so fine for raising horses and as our use for them increases yearly.

The plantation has now become very extensive and we have to cart the weed further for the indigo field on the Guana. Although it is but narrow, it will this year extend half a mile beyond the old potato field where the land is loaded with live oak timber. The heavy timber I have not touched but in time it must come into play. But at present the Guana clearing is almost totally from the British thicket yet it is worse to prepare for planting than the best timbered hammock in the country. . . .

I received the Negro cloth, medicines, rough irons and two casks of porter. The cloth was extraordinary bad, so bad that I did not think worth making it up for the men. The women have had jackets and petticoats made of it, but men must have jackets and breeches supplied from Mr. Paine’s store. The cloth will turn out to very good account although not fit for clothing in the first place. Every man had a pair of boots made of it and it will do very well for indigo draining cloths, much cheaper than could be purchased. If I desired that cloth should be sent it was wrong for the clothing made up is better as the making here comes too high and to have them made at the plantation by the wenches who can sew is too tedious.

Negroes in general are healthy, they are well fed, look well and are contented. I endeavor to encourage them and they deserve it. Very little flogging is used as indeed there is no occasion for it. A carcass of beef with all its appurtenances was sent them yesterday with some rum for their Christmas.

…I am told to put you to more expenses. I should be glad of another boiler I care not whether iron or copper as iron will do as well and will come lower. The only difficulty is fixing the cock in the iron boiler which is necessary as a [safety measure]. The one we have is a good size and in all respects has done well. I have tried many experiments for improving the making, but I have not found anything that works as well as boiling. Sundry people have now begun to follow it, but they laughed at me when they first heard of it….

The old sloop is good for nothing. I mean the hull and her rigging and I will put it to sale at vendue or dispose of it.

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, October 5, 1775 (from Peter Force, American Archives, Vol. 4).

The Alatchaway Indians are in St. Augustine at a bad time for me. While they are in town I am trying to make indigo….The people at the plantation are obliged to be upon foot night and day in order to save as much of the indigo from the worms as possible, and it is not in my power to give them any assistance until these savages are gone from Town.

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 29 October 1775:

Captain Wallace is leaving this port with a cargo of oranges. They will probably meet with good market if they do not spoil on passage. I sent you ten young hogs, three dozen fowls and four turkeys with twenty-five bushels of corn to feed them. I would have been glad to have sent you more poultry but they are scarce now at the Villa….Mr. Forbes will send fish and oranges.

Mr. Mulcaster and Mr. Yeats have desired me to meet with Governor Patrick Tonyn to settle on furniture. It should have come from themselves but it was put upon me and it shall be done. It is a shame it was not settled long ago. Your slaves Peg Sue and Alexander have been in his service since his arrival and have met with treatment they were not used to. If any of them should die which would be no wonder notwithstanding their being once strong, healthy Negroes, whose loss would it be? I do not mean to excuse myself by laying the blame on others but I need not tell you the reason why I could not do much in this matter although my inclination is good. Parson, Mulcaster and Yeats write by this opportunity and will give you all the news in this matter….

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 15 February 1776:

Florida is feeling the ill effects of the fighting in Georgia and Carolina. Provisions of every kind but beef are scarce in town, many of the settlers in some degree of distress….Planters have [bare] sufficiency of provisions for their Negroes though on this score we are pretty easy at the villa but if the province is not in some means supplied with corn some other people will be in a bad way until the new crop is ready. Every resource from Georgia or Carolina has been cut off long ago.

. . .

Your indigo is sorted at the plantation and ready to be shipped out by first opportunity….Bremner, who I had a very good opinion of and thought would turn out to be a great service, has gone off. He has left your employ as of the first of November to become an under clerk to Penman. This transaction was brought about by the help of Spencer and his wife while I was employed at the Indian meeting on the St. Johns where I received a letter from the youth signifying his intentions, which is enclosed. He had no reason to change his situation except for my treating him too kindly. In this matter I think myself exceedingly ill used by these two reptiles, Man and Penman….and I am certain they owe you…

The furniture matter with the governor is not settled yet, Mulcaster is looking into it right now.

Alexander and Peg have run away. Alexander has been gone about two months, and Peg about three weeks. I have some reason to think they have been lurking about the Villa. Rewards have been advertized for their capture….I look upon it as a piece of cruelty to let them fall into such hands. If you were acquainted with the manner in which they have been used all would look upon it as cruelty to have put them into such hands.. Mr. Yeats should be given directions, since he is less dependent [on Governor Tonyn] than I am. I think you stand a chance to lose some of them. Sue and her child has been at St. Johns as a field slave since last May.

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 24 February 1776:

I have sent your indigo to St. Augustine to be shipped when a vessel sails that way and safely….

I am glad to hear Francis and Baptist [slaves who accompanied Grant to England in 1771] are so much reformed. It will be some little saving and a great satisfaction in your present situation. Their old messmates Alexander, Peg and Sue would rejoice to be along with them and if I can answer for them, would behave with ten times the humility and submissiveness they formerly had at your house at St. Augustine. Alexander had been put at his own choice to go to the plantation or to live in town and I promised to be kind to him if he went to the country.

For some weeks past poor Alexander and Peg have been very glad for a little protection at the Villa to save their backs from the cowskin. I was not displeased to find by your last letter that they were to remain your property till you should approve of the price offered for them, as in that case you will hardly dispose of them in the way you intended. I mentioned something about them in my last letter. The governor [Tonyn] heard of them being at the Villa and wanted them back but Mr. Yeats and I thought it would be wrong to send them back to where they had been so severely disciplined and where they had still worse to expect if they had been returned.

James Grant to Alexander Skinner, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 23 April 1776:

[I want you] to give all the attention necessary to my business and your own….If I live you may trust to me. Before I left London in case an accident should happen to me I settled my affairs, and have left you a legacy of five hundred pounds sterling. I think upon the whole that it will be better for you to be totally independent of the governor, for I shall lose a great deal more by your absence from the Villa, than your salary from me will amount to.

[Grant calls Bremner an “ungrateful little rascal” and vows to not forgive him or “his seducers” and to go hard on them in future].

I will neither sell or hire Alex, Peg and Sue to governor Tonyn, and have directed him…to send them to the Villa within 24 hours after he received my letter…“where they are to live in future in peace and quiet under your direction so you may dispose of them, or make what use of them you please.” [Grant expressed anger that David Yeats left Alexander, Peg and Sue with Governor Tonyn for so long and that Sue had been used as a field slave, and said Skinner’s involvement had been concealed]. Mulcaster and the Parson will be suspected. Tis a cross talk if the Governor sees it — but I care not a farthing about him….His declining to settle about my furniture before Mulcaster left the Province is astonishing, he has had it in his possession near three years, and I left the mode of payment to himself. . . .

I have great confidence you will do in my affairs whatever appears to you to be best, I put you under no restrictions and I shall not make you responsible for the event. You will succeed if you can and I can’t expect more….

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, 9 September 1776:

Lady Egmont’s plantation has been broke up and the houses burned by the Rebels and all the plantations on the west side of the St. Johns River are evacuated. Rebels have got as far as the Cowford and it has been stated their intention is to plunder and destroy all the plantations on the river which is probable they may effect as there is only a detachment of 100 men to oppose them, and no naval force on the river except a ten gun sloop which the governor has been obliged to take in and pay at the rate of 200 Sterling a month besides finding provisions.

The St. Johns schooner has come here to be cleaned and have such repairs made as are necessary. She is very damaged and very incomplete in stores and rigging as there are no supplies to be had here. The Seminole Indians had some time ago been seemingly well disposed but some late talks we have had with the Nation have given them a different turn and they do not seem heartily engaged in the cause. So that upon the whole I expect nothing more than that whole settlements in the country will be destroyed if we are not speedily reinforced with some good troops and an able force, for the Indians are not much to be depended upon and the more they see us distressed the more willing they will be to interfere.

I have yesterday ordered all the Negro children at your Excellency’s plantation to be brought to Town [along with] all the cured indigo. There is a good flat ready for all the Negroes to embark themselves upon the first alarm which is to be given by two watchmen posted between the two rivers at a mile’s distance from the plantation with horses ready to mount as soon as they discover any party of men approaching. This is the only road these rascals can come by, which means I think there is no danger of the Negroes falling into the hands of the Rebels. Nor need they quit the plantation until there is a necessity of it. But these maneuvers suits ill with the planting business and will spoil the crop as everybody employed are in continual fear and on the most trifling occasion everyone takes to their heals. I intend to send the first crop home by Lofthouse who says he intends to sail about ten days from now.

Skinner to Grant, St. Augustine, January 7, 1777:

Peg, Sue, and Alexander are at the plantation. Peg has been unwell ever since she was set at liberty. Sue is in the field and Alexander starts as cook & baker in place of Ragu who chooses to work in the field. He has grown a very stout fellow and makes an excellent field slave.

I never longed so much to hear from your Excellency as I have of late. Everybody is impatient to hear what the troops are doing. I pity your situation on account of the cold. I’m so cold sitting by the fire my fingers will hardly hold the pen while I’ve been scrawling out this letter..

Skinner to Grant, 30 April 1777 St. Augustine:

I wrote to you so often I now begin to despair of ever hearing from you till this unhappy American war is ended. Still, you shall hear from me by every convenient chance. This is by way of Captain Wallace who hopes to see you if he is able to. He’ll have other news.

All is well at the Villa and planting goes on tolerably. Were it not for frequent alarms from our friends in Georgia who still continue their threats and keep sending in little plundering parties which can not be kept from the knowledge of the Negroes and thereby creates such confusion it is impossible to manage the planting business as it ought to be. We are in the strongest approachment of heavy attack from troops from Georgia supported by troops from Carolina. What will be the result time must determine.

The latter part of your indigo crop is not yet sent home as no opportunity offered, and also since freight and insurance is high the market is low.

McKenzie wants to purchase Peg on account of a Negro fellow belonging to him who has found her. He desires that I should write you about it and in meantime I have hired her to him at £25 Sterling per annum as the Negro fellow would not stay from her. She could hardly be worth so much employed in any other way. If you choose to part with her you will have only to fix the price and let me know. She has now recovered her health and looks as well as she ever did.

. . .

Accounts from the St. Johns River just arrived that the Rebel Army is crossing St. Marys River upon their march into this province. I’m uneasy about the Villa. All I can say is what I have often said before that we shall do as well as we can.

Skinner to Grant, The Villa, 30 September 1778:

We are now scraping up as much indigo as we can at the Villa, where my presence is more frequent than usual. I am not expecting a great crop as the land will not give it with all the care and industry possible. I must therefore try for a crop of indigo at the head of the Guana River next year. The Lord knows the land there is very good, though the quantity is small. It appears to be the most convenient spot for I would not choose to have the Negroes far from Town in these times.